Who Takes Mental Health Days, and What Are the Common Triggers?

We surveyed people to find out what a mental health day can do for daily stress and happiness.

Almost 60% of American workers have recently felt symptoms of burnout from their jobs: emotional exhaustion, cognitive weakness, and physical fatigue. In fact, only 6% of Americans don’t report feeling stressed at their job. Stress costs businesses money, wastes your time, and can ruin your health, even leading to things like infertility and cancer. With mounting stress levels for so many people, stepping aside and taking a day to regroup and recharge is indispensable for daily functioning.

But, when you feel stressed, exhausted, and overwhelmed every day, how do workers decide when it’s time to take a step back? We asked 763 people who took a mental health day this year to find out.

Jump to:

Key takeaways

Our survey revealed several important insights, including:

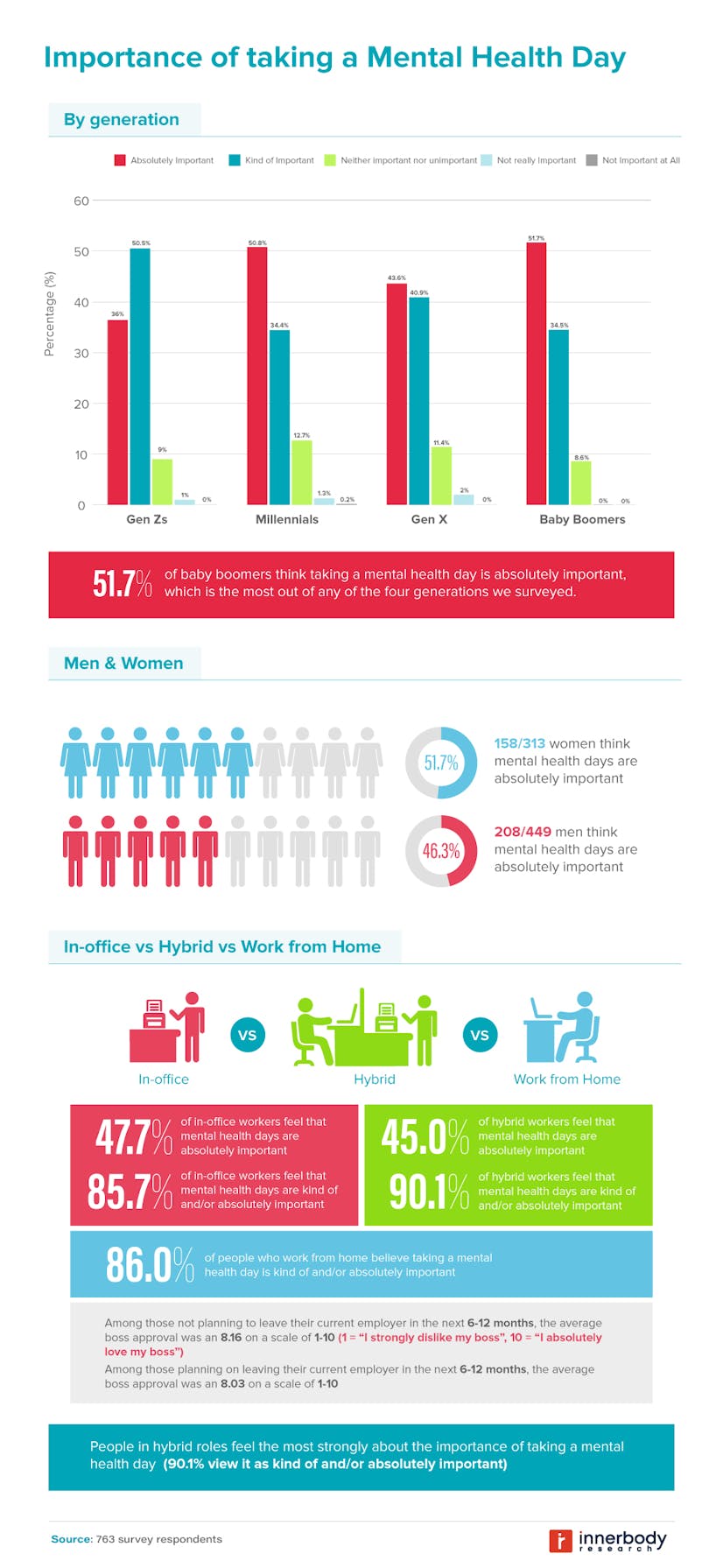

- Baby boomers are the most likely (51.7%) to feel that mental health days are “absolutely necessary,” and Gen Z is the least likely (36.4%).

- More women (50.5%) feel it’s important to take mental health days than men (46.3%).

- People working in hybrid roles feel strongest about the importance of taking a mental health day.

- Most respondents took mental health days due to more stress than usual at work (66.4%), followed by general burnout (51.8%).

- Taking a mental health day more than doubled the number of people who rated their happiness with a top score.

Mental health day triggers: an overview

There are dozens of reasons that people take mental health days. Sometimes, mental health days are an opportunity to catch up on the rest of life that falls away when we are too overwhelmed by busy work schedules; other times, it’s an opportunity to rest and heal when our mental health fails.

No matter the source, chronic stress can have devastating health effects, as increased cortisol levels and high blood pressure over the long term wreck your health. This includes cardiovascular, immune, digestive, and mental health, among others. Finding the right stress management strategies can help stave off burnout and chronic stress long-term, but sometimes you just need a moment to breathe. That’s where mental health days come in.

Mental health days are not long-term solutions, but they can help you identify a better strategy for a more serious problem or just relax after a period of heightened work stress.

Below, we’ll discuss the major factors that lead people to take a mental health day.

Generational breakdowns

The graphic above shows the generational differences in thinking about the importance of mental health days. (Note that not every generation adds up to 100%, as not every participant answered this question.)

Baby boomers weren’t the only group with zero people who think taking a mental health day isn’t important. No one in either Gen X or Gen Z thought mental health days weren’t important at all. And only one millennial thought that taking mental health days is “not important at all.” Overall, no more than 2% of any age group felt that taking mental health days wasn’t very important.

The lack of disdain for mental health days makes sense considering that we gave this survey to those who’ve recently taken a mental health day: people who think it’s essential to care for their mental health by taking a break from work are more likely to step away from the office. That said, these results provide intriguing insights, considering baby boomers’ notoriety for perpetuating stigmas against mental health and Gen Z’s typical openness about mental health.

While this survey doesn’t confirm or deny generational stereotypes, it does help us understand who’s taking mental health days — and that millennials’ and baby boomers’ feelings about mental health days are more closely aligned than their similarly-aged counterparts. For example, according to the American Psychological Association’s Stress in America survey, Gen Z is the least likely to say that their mental health is excellent or very good and the most likely to seek therapy.

Our results may indicate that mental health days are more widespread across Gen Z. Conversely, not many rated mental health days as “absolutely important.” There may be more concepts Gen Z considers crucial for their mental health than just taking a day off work, especially compared to previous generations.

Gender differences

The gender differences in the workforce don’t stop at hiring discrimination, pay gaps, and glass ceilings. While there are more stay-at-home dads, women are often still expected to carry the burden of household work, spending an average of 37% more time on unpaid labor than their spouses, even in egalitarian households. Gender differences and discrimination in the workforce only push this stress. Women consistently report higher levels of work-related burnout and lower satisfaction in their careers (34% vs. 26% in 2021), even in conventionally high-paying jobs like doctors.

Our survey found that 50.5% of women, compared to 46.3% of men, rated mental health days as “absolutely important.” Considering the higher rates of job-related burnout among women, this statistic is unsurprising.

What triggers employees to take a mental health day?

There are several reasons someone might take a mental health day. We’ve broken down the top five from our survey below.

Feeling symptoms of burnout like a jaded attitude and lack of confidence in their work contributed to more than half of our participants’ reasons to take a mental health day.

Most people took a day off after experiencing higher stress levels than usual at work. This likely allows for more time to decompress and regroup.

When employees feel overwhelmed by the amount of work on their plate, they’re more likely to take a mental health day.

If an employee just isn’t happy at their current job due to any number of factors, they’re more likely to take a mental health day. This may be to step away from an unhealthy workplace or because those unhappy at work are more likely to experience bad feelings that can lead to burnout, among other reasons.

A mental health day can be a great way out if someone just needs an extra day off. It can allow an employee to relax at home without any pressure or expectations.

Deadlines

Out of our respondents, 72.1% rated their workplaces as more deadline-focused than average. However, workplaces with more intense deadlines are more likely to induce higher stress levels. A 2017 survey found that 82% of people labeled their job “on the more stressful side,” and 30% reported that strict deadlines played a large role in that analysis. Over 17% said their job was stressful because others’ lives were at risk.

Only 7.6% of our respondents with a deadline-focused workplace work more than 50 hours a week. But a vast majority of them took mental health days due to higher levels of burnout, more stress than usual, and feeling unhappy at work.

Location

Work location plays a small role in the importance of mental health days. 90.1% of hybrid workers feel that mental health days are “kind of” or “absolutely important,” whereas 85.7% of in-office workers feel that way. However, more in-office employees find it “absolutely important” (47.7% versus 45.0% of hybrid workers). Those who work from home sat between hybrid and in-office workers, as 86% said taking a mental health day is “kind of” or “absolutely important.”

While working modality doesn’t make or break a person’s opinion on mental health days, there is an observable trend: those in more flexible environments are more likely to find mental health days important.

Job satisfaction

Mental health days can sometimes indicate that a job isn’t the right fit. Needing to take time off from burnout, like 51.8% of our survey’s respondents, can be unsustainable. However, how much an employee likes their boss seems to make no difference in whether or not they plan to move on from their position.

When asked to rate their boss on a scale from one to ten, where a score of one meant they “strongly disliked” their boss and ten meant they “absolutely loved” their boss, the average score sat around an 8 for our respondents. Those planning to leave had equally strong positive feelings about their bosses as those staying in their current positions (8.03 versus 8.16 on a scale from one to ten, respectively).

Planning a mental health day

Gone are the days of practicing a cough to convincingly call in sick. Many workplaces now view mental health days as legitimate reasons to take a day off, especially when you’re struggling with your mental health.

However, that doesn’t mean taking the day off is any easier. Slightly less than half of the participants (48.9%) said they still call in sick when taking a mental health day. Other methods included:

- Asking for a personal day (35.9%)

- Using paid time off (14%)

- Something else (1.3%)

Respondents were almost perfectly split between taking one day and several days. 49.4% report usually taking more than one mental health day at a time. This difference depends not only on personal preference but also on your ability to take time off, which varies dramatically based on your job. Low- and mid-level workers making $60,000 or less annually are the most likely to experience burnout. They are the least likely to have ample sick and personal days to recover, leading to even more burnout.

Missing a day in the middle of the week can make one long week feel like two short ones, but a self-made long weekend can allow you to really relax and unwind. Our survey found that most people took mental health days on Mondays (55.0%) and Fridays (43.9%), giving themselves a long weekend. Thursdays (26.7%) were the least popular choice for mental health days, which makes sense — if you only have one day to relax and recover, leaving one day between your mental health day and the weekend might lead to a stressful Friday.

What do people do on a mental health day?

When you’re already burned out, planning what to do may seem just as insurmountable a task as taking the day off in the first place. Luckily, 70% of our survey respondents said that they like to rest and relax at home on mental health days. Without a trip, appointment, or chore on the docket, taking it slow around the house can give your mind the total reprieve it needs to rebuild your focus and concentration.

The number of people who like to laze at home varied slightly by generation. Baby boomers were the most likely to report staying at home (75.9%), whereas less than half of Gen X-ers (46.3%) found that same joy. Most millennials (72.9%) and Gen Z-ers (61.6%) felt similarly.

Staying home in your pajamas isn’t the only way to spend a mental health day. Some other things people like to do to recharge include:

- Going out alone or with friends

- Doing hobbies

- Catching up on postponed errands

- Going to the gym

- Listening to music

- Shopping

Anything that helps to refill your emotional and physical energy will help you feel your best after a mental health day, no matter what it looks like.

Lasting impacts of a mental health day

Our survey respondents were asked to rate their general happiness on a scale from one to ten (one being “very low,” and ten being “very high”) both before and after a mental health day. Before taking a mental health day, one-third of respondents rated their general happiness at a five or below. Of these people, 91.5% then rated their happiness at or above a five after their mental health day. This is a huge jump, meaning huge improvements in daily quality of life. (That’s less than 20 people out of hundreds who still felt low afterward.)

The number of people who chose a rating of ten more than doubled after taking a mental health day. This wide-ranging improvement shows a lot of promise — and immediate benefits — for both short- and long-term mental health. No matter what you do on your mental health day, there are clear advantages to taking one.

When a mental health day doesn’t help

Sometimes, taking a day off (or three) is enough to lift spirits and calm a racing mind. However, some people will avoid taking mental health days because they collapse once they stop moving. If this sounds like you — or if taking a mental health day makes you feel worse — there might be something more serious at play.

As much of a buzzword as it’s become, burnout from work is a serious concern. It’s classified as an “occupational phenomenon” by the World Health Organization and contains three parts:

- Emotional exhaustion

- Cynicism, detachment, and lack of satisfaction from work

- Lack of confidence in the ability to do work-related tasks (professional efficacy)

Chronic stress and burnout can easily lead to mental illnesses like depression and anxiety. Signs to watch out for include:

- Feeling numb or irritable

- Loss of interest or pleasure in all of your activities, not just work

- Sleep disturbances (sleeping too much or too little)

- Significant (5%+) unintentional weight changes

- Difficulty thinking, concentrating, or making decisions

- More fatigued than usual, or more easily fatigued

- Excessive feelings of worthlessness or guilt

- Slow or racing thoughts

- Restlessness or feeling “on edge”

- Worrying about things in every aspect of life, not just work

- Worry that feels uncontrollable

If your need for a mental health day has become a mental health month (or longer), these signs may be on the horizon. Don’t be afraid to reach out — many employers offer low-cost access to therapy through insurance and EAP plans. You can even access therapy from home if packed work days contribute to your burnout.

Methodology

We surveyed 763 people about whether or not they have taken a day off from work within the past year for mental health reasons. If so, what were the most common answers as to why this mental health day was necessary? Was it mostly due to burnout, more stress than usual, or just needing a day to relax? We also analyzed which industry has the most people taking mental health days and whether or not having a deadline-focused job plays a role in the number of mental health days needed.

Fair use statement

Innerbody Research is committed to providing objective, science-based suggestions and research to help our readers make more informed decisions regarding health and wellness. We invested the time and effort into creating this report and other mental health-related guides to raise awareness for mental health and wellness. We hope to reach as many people as possible by making this information widely available. As such, please feel free to share our content for educational, editorial, or discussion purposes. We only ask that you link back to this page and credit the author as Innerbody.com.

References

-

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Retrieved July 8, 2022, from https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

-

de Beer, L. T. (2021, June 9). Is there utility in specifying professional efficacy as an outcome of burnout in the Employee Health Impairment Process? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. Retrieved July 8, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8296033/.

-

Cleveland Clinic. (2022, April 11). Is taking a mental health day actually good for you? Retrieved July 8, 2022, from https://health.clevelandclinic.org/is-taking-a-mental-health-day-actually-good-for-you/.

-

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Mental health. Retrieved July 8, 2022, from https://www.who.int/health-topics/mental-health#tab=tab_1.