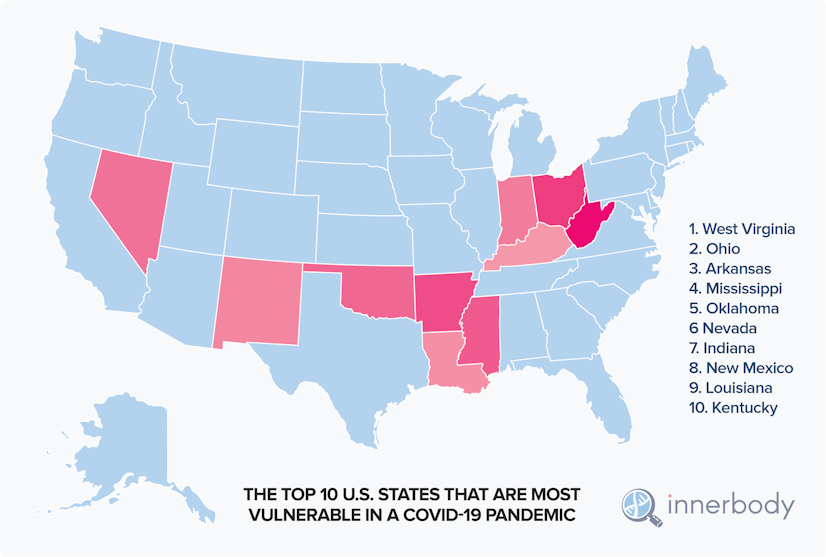

These states are the most vulnerable in a COVID-19 pandemic

Our research team dives deep into the latest government statistics and ranks each U.S. state based on vulnerability

As the entire country and world grapple with the COVID-19 pandemic and what it means for us, our loved ones and various communities, Innerbody Research has launched an extensive study. Our aim is to assess and rank the vulnerability of each of the 50 states in the context of this novel coronavirus pandemic.

To conduct our study, we closely examined the latest data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of Housing and Urban Development, American Hospital Association, Census Bureau, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, among many others.

Rankings are based on analysis of a multitude of data sets, culminating in 20 different ranking factors that extend across three broad subject areas of relevance to a state’s defensive posture against COVID-19:

- Initial health emergency preparedness of each state

- Relative vulnerability of a state’s population

- Environmental factors such as population density

The combination of these three broad ranking areas leads to our calculation of Overall Vulnerability Score.

To learn more about each of the 20 factors we used, along with their relative weighting, please see the How We Collected Data and Developed Our Rankings section below.

It is important to note: no matter where your state ranks, we all have an obligation to heed the advice of local and federal health officials and take this pandemic seriously. Our actions mean just as much to the outcome of the pandemic as any factors in this study. Please follow the advice of your local health leaders and state and federal authorities.

The Top 10 states most vulnerable in a COVID-19 pandemic

Based on this analysis, West Virginia ranks as the number one most vulnerable state in a COVID-19 pandemic. Among the major factors contributing to its score are:

- Very high rates of underlying health conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease and chronic respiratory disease (West Virginia ranks second to last for its cancer rate, and worst in the nation for chronic respiratory disease rate).

- A population that skews older (only Florida and Maine have a higher percentage of population over 65 years of age).

- Second-to-lowest level of health emergency preparedness (behind Alaska).

- Third worst level of healthcare access.

- Enough population density to magnify the risk posed by the aforementioned factors.

With an Overall Vulnerability Score of 74.1, West Virginia ranks far worse overall than the next most vulnerable state, Ohio, which ranks second at 62.2. In terms of health emergency preparedness, the Buckeye State is the third worst in the country. It ranks among the bottom ten states for heart disease rate and subpar for its rates of several other significant underlying health conditions.

Ohio has a higher-than-average percentage of its population over the age of 65. It’s also one of the ten most densely populated states in our country. On the positive side, Ohio has an above-average number of hospital beds relative to its population.

Rounding out the 5 most vulnerable states in our study are Arkansas (60.6), Mississippi (58.7), and Oklahoma (57.7) at 3rd, 4th and 5th, respectively. They comprise the bottom three states in overall environmental vulnerability.

Arkansas and Oklahoma suffer from high rates of underlying health conditions. Both are in the bottom five for collective, high-risk underlying health factors among all states, with Oklahoma ranked lowest of all for its heart disease rate. Mississippi is also in the bottom ten states in our analysis of underlying health risk of its population, with the third-highest rate of diabetes in the country (just ahead of Arkansas).

Mississippi, meanwhile, ranks dead last in healthcare access, with Arkansas nipping at its heels.

The 10 least vulnerable states in a COVID-19 pandemic

On the other end of the spectrum, the state our study concludes is least vulnerable in a novel coronavirus pandemic is Utah, with an Overall Vulnerability Score of 17.2.

Utah owes its best-in-class distinction to a combination of characteristics including the following:

- Relatively great baseline health of its population (Utah has the lowest rates of hypertension and cancer, and among the ten lowest rates for heart disease, chronic respiratory disease and diabetes).

- Beneficial environmental factors such as low population density.

- A robust healthcare system, ranked in the top ten for access to healthcare.

- The lowest percentage of the population over 65 years of age.

Colorado (22.8) is the next least vulnerable state according to our study. In our assessment of underlying health risk, it is third best in the country. The Centennial State enjoys the lowest rate of diabetes and the second-lowest rate of hypertension (behind Utah). Solid access to healthcare and a relatively low population above age 65 also help keep it less vulnerable in a COVID-19 pandemic. One risk for Colorado, however, may be its subpar number of hospital beds per capita.

Rounding out the 5 least vulnerable states are Nebraska (26.1), Massachusetts (26.2), and Maryland (29.9), which very narrowly edged out Virginia. It was striking that two neighboring states – Virginia and West Virginia – are nonetheless so divergent in their vulnerability during a novel coronavirus pandemic.

In terms of emergency preparedness, Nebraska is second only to Massachusetts. Environmental factors like population density are very favorable and Nebraska’s population enjoys low rates of major underlying health conditions like heart disease and diabetes. Nebraska is also equipped with the fifth-most hospital beds relative to its population.

Maryland’s percentage of its population above age 65 is the tenth lowest in the country, while access to healthcare is the eighth best. Massachusetts has the second-best healthcare access nationwide, and its rates of heart disease and chronic respiratory disease are among the best.

Best and worst states in select ranking factors

Ranking all 50 states on COVID-19 virus vulnerability

Below is how each of the 50 states ranks for overall vulnerability in a COVID-19 pandemic – 1 being most vulnerable, 50 being least vulnerable – along with how each compares across our three broad subject areas: High-Risk Population, Emergency Preparedness, and Social & Physical Environment.

Asking the experts

In the process of developing our 20 ranking factors for this study, our own research team incorporated the guidance of some of the world’s leading experts in infectious diseases. Below is what some of them had to say on some of the factors that influence a state’s vulnerability to a COVID-19 pandemic.

Age and underlying health conditions as risk factors

“It’s very clear that this virus has greater mortality and morbidity in older individuals and those with chronic conditions.”

Mark Mulligan, director of NYU Langone Health’s division of infectious diseases and immunology

“Older people are more likely to have serious underlying conditions that also put them—and younger people—at risk of complications from COVID-19. Cardiovascular disease, diabetes and lung diseases all tax the body, making infections harder to fight off. The system is just not able to put up with that much of an assault.”

Bruce Ribner, director of Emory University School of Medicine’s Serious Communicable Diseases Unit

“All you folks older than 60 and those who have underlying illnesses, you ought to do personal mitigation starting now. It’s imperative that the population understand that now is the time to get serious about avoiding group events, and to become a bit of a hermit. If I’m older, and have underlying illnesses, then I’m the kind of person that this virus makes more seriously and even gravely ill.”

Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University

Importance of social distancing – and the environmental and infrastructural challenges that make it difficult

“Every single reduction in the number of contacts you have per day with relatives, with friends, co-workers, in school will have a significant impact on the ability of the virus to spread in the population.”

Dr. Gerardo Chowell, chair of population health sciences at Georgia State University

“We need to avoid social mixing — both individually and collectively. Besides washing their hands, individuals need to keep a certain physical distance from others (about four feet) and avoid touching each other. People should work from home if they can, and avoid non-essential meetings and travel. These are prudent steps anyone can take on their own. This kind of social distancing can help “flatten the curve,” meaning it will lead to a more gradual rate of infection and thus prevent our healthcare systems from being overwhelmed.”

Dr. Nicholas A. Christakis, Sterling Professor of Social and Natural Science at Yale

“Rural populations have less means to contract it [coronavirus], but rural populations have less means to treat it.”

Eva Kassens-Noor, professor of urban planning, Michigan State University

“Social distancing is something often talked about but only works well for the urban middle class. It doesn’t work well for the urban poor or the rural population where it’s extremely difficult both in terms of compactly packed houses, but also because many of them have to go to work in areas which are not necessarily suitable for social distancing.”

Dr. K. Srinath Reddy, adjunct professor of epidemiology, T.H. Chan School of Public Health at Harvard University

“The idea that we can go to the countryside to protect ourselves is a bit of a myth, because it doesn’t exist like it used to.”

Roger Keil, professor of urban studies at York University in Toronto

Health infrastructure, pandemic preparedness, and heeding the advice of health officials

“It is important to remember that COVID-19 epidemic control measures may only delay cases, not prevent. However, this helps limit surge and gives hospitals time to prepare and manage. It’s the difference between finding an ICU bed & ventilator or being treated in the parking lot tent.”

Professor Drew Harris, Thomas Jefferson University College of Population Health in Philadelphia

“In many places around the country, the fiscal austerity that many state and local governments have been living under has eroded that [public health] infrastructure.”

Aaron Katz, University of Washington health policy expert

“How are we going to be able to handle the surge of patients that need complex care if these rural hospitals have no place to transfer those patients that need more tertiary services?”

Brock Slabach, National Rural Health Association

“Be fast, have no regrets. You must be the first mover. The virus will always get you if you don’t move quickly. If you need to be right before you move, you will never win. The problem in society we have at the moment is that everyone is afraid of making a mistake. Everyone is afraid of the consequence of error. But the greatest error is not to move. The greatest error is to be paralyzed by the fear of failure. Perfection is the enemy of the good when it comes to emergency management. Speed trumps perfection.”

Dr. Michael Ryan, W.H.O. Executive Director, leading expert on epidemics

“I want people to assume that I’m over- or that we are overreacting, because if it looks like you’re overreacting, you’re probably doing the right thing, because we know from China, from South Korea, from Italy, that what the virus does, it percolates along and then it takes off.”

Dr Anthony Fauci, Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

On the importance of testing

“As I keep saying, all countries must take a comprehensive approach, but the most effective way to prevent infections and save lives is breaking the chains of transmission. And to do that, you must test and isolate. You cannot fight a fire blindfolded, and we cannot stop this pandemic if we don’t know who is infected. We have a simple message for all countries: Test, test, test.”

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director General, World Health Organization (WHO)

Some caveats

We want to emphasize that these rankings are not meant to forecast any pandemic outcomes, but rather just to illustrate how a variety of public health, infrastructural and environmental factors can create local climates that are more or less inherently vulnerable in times of a pandemic like COVID-19. There is no way that this study could forecast any outcomes, because the study excludes too many factors that are fundamental to the outcome of the pandemic.

We could imagine the COVID-19 response in each state as one of 50 different states. We aren’t forecasting the final product – the cake coming out of the oven – but instead analyzing the ingredients that went into the making of each cake.

So it’s important to acknowledge, up front, that those ingredients don’t by themselves determine the final outcome of the cake; you could use ingredients from a great cake recipe but end up baking it at an improper temperature, or using the wrong baking sheets.

This study pertains strictly to COVID-19

While some of our ranking factors would be vitally important if we analyze safety from other pandemics, we formulated this study to focus on the characteristics of COVID-19 specifically. The vulnerability rankings will only be of interest or use within that specific context.

For instance, our study considers what proportion of a state’s population is over age 65, because data indicates that seniors are at greater risk of life-threatening illness from this particular virus. With other viruses, advanced age might not be a factor at all or might be a positive factor (sometimes a virus is deadlier for young people).

Our study also weighs factors related to the rates of serious underlying health conditions like cardiovascular diseases, lung disease and diabetes. Data indicates that people with preexisting health conditions such as these – no matter their age – are at greater risk of severe illness from COVID-19. These factors would be relevant in many other studies of pandemic vulnerability, though they might be weighted differently.

An analysis of vulnerability in a different pandemic could likely result in a much different ranked list.

Our social behavior

This study cannot account for the social behaviors of our states’ populations during this pandemic. And yet the outcome of this pandemic depends to a large extent on:

- How well we adhere to proper handwashing and hand sanitizing

- Our ability to shelter in place or maintain proper social distancing, even when asymptomatic

- How effectively we shield our elderly and vulnerable populations from exposure

- How well we can adhere to other important advice from public health officials

Our own discipline will make a huge difference here. A state might be on the best footing in terms of pandemic preparedness and be ranked well in our study, for instance, but could ultimately be less safe and fare much worse than states with less robust health infrastructure if its population behaves in ways that dismiss or downplay the risk of infection.

A note about densely populated areas

Population density can turbo-charge transmission of disease like COVID-19, which is why it is one factor in our study.

Historically, this unique vulnerability (as compared to rural and suburban areas) led to cities being hit hard, while sparsely populated areas were largely spared. But our world has changed dramatically through interconnectivity and the shipping of goods and supplies.

And not just interconnectivity, but rapid interconnectivity. Products and people travel from across the world and arrive in remote, rural areas well within the timeframe in which virus can survive on surfaces or people can be contagious while still asymptomatic.

So, rural safety in the end – relative to urban living during this pandemic – does largely depend on factors our study can’t assess (mainly, our discipline in adhering to restrictive social behaviors and also the policies of our state and federal authorities that may curtail our interconnectivity).

Also worth noting: in addition to population density, our study also includes factors related to health infrastructure for obvious reasons, and in our country the two often go hand-in-hand.

About age and COVID-19

While the elderly – and those with underlying health conditions like high blood pressure and diabetes – are considered at greater risk of becoming seriously ill if infected, this does not mean that younger populations are not at risk. So far in the United States, 38% of hospitalizations from COVID-19 are people ages 20-54. And while half of patients in the ICU for novel coronavirus are over 65 years old, that still leaves half of ICU patients who are younger. So, while the elderly are statistically at greater risk, COVID-19 also poses a very real risk to younger Americans.

Testing, testing, testing

That’s what the leaders of the World Health Organization (WHO) emphasize is of fundamental importance in combating the novel coronavirus around the world. Unfortunately, our testing capabilities as a nation were inadequate and only now are we starting to ramp up meaningfully. And even now, we are nowhere near the level of testing that epidemiologists and WHO officials advocate.

States that have few reported cases of COVID-19 might have unreported cases. This can lead to a false sense of security, making these states potentially less safe than states that have conducted enough testing to determine at least the presence of infection. Experts believe that COVID-19 was circulating in the United States potentially for weeks before testing confirmed the first domestic case.

Our ability to test reliably in the necessary volumes is an important component of how quickly we can overcome the pandemic or how hard certain states might be hit. Like the aforementioned social behaviors, it is not a factor in this study.

In our opinion, states would do well to assume that COVID-19 is everywhere now, even if unreported.

Medical equipment and supply shortage

Some of our ranking factors assess strengths and weaknesses relative to other states. A state may be better prepared for pandemic relative to other states, and yet it’s possible that no state is fully prepared with sufficient equipment and supplies (ventilators, hospital beds, masks) that are vital to preventing spread and treating illness. Even our best systems run the risk of being overwhelmed, if we don’t soon slow the spread of novel coronavirus and flatten the curve of infection. Failure to confront the pandemic aggressively enough at this stage could mean that even the most robust health systems in well-prepared states are overwhelmed.

Methodology: How we developed our rankings

High-Risk Population Rank: 40% total weight

Percent of Population Over 65: 12% weight

- Measures: Percentage of adults who are 65 years or older

- Source: United States Census Bureau’s American Community Survey

Coronary Heart Disease Rate: 8% weight

- Measures: Coronary heart disease deaths per 100,000 people who are 35 years or older

- Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Cancer Rate: 4% weight

- Measures: Number of cancer cases diagnosed per 1,000 people

- Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Diabetes Rate: 4% weight

- Measures: Percentage of adults (age adjusted) diagnosed with diabetes

- Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Chronic Respiratory Disease Rate: 4% weight

- Measures: Chronic respiratory disease deaths per 100,000 people

- Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Hypertension Rate: 4% weight

- Measures: Prevalence of hypertension among adults 18 year or older

- Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Homelessness rate: 4% weight

- Measures: The number of homeless adults, age 18 and older, per 1,000 people

- Source: United States Interagency Council on Homelessness

Emergency Preparedness Rank: 30% total weight

Community Planning & Engagement: 5% weight

- Measures: Actions to develop and maintain supportive relationships among government agencies, community organizations, and individual households; and to develop shared plans for responding to disasters and emergencies

- Source: National Health Security Preparedness Index

Information Incident Management: 5% weight

- Measures: Actions to deploy people, supplies, money, and information to the locations where they are most effective in protecting health and safety

- Source: National Health Security Preparedness Index

Healthcare Delivery: 5% weight

- Measures: Actions to ensure access to high-quality medical services across the continuum of care during and after disasters and emergencies

- Source: National Health Security Preparedness Index

Health Security Surveillance: 5% weight

- Measures: Actions to monitor and detect health threats, and to identify where hazards start and spread so that they can be contained rapidly

- Source: National Health Security Preparedness Index

Countermeasure Management: 5% weight

- Measures: Actions to store and deploy medical and pharmaceutical products that prevent and treat the effects of hazardous substances and infectious diseases

- Source: National Health Security Preparedness Index

Environmental & Occupational Health: 5% weight

- Measures: Actions to maintain the security and safety of water and food supplies, to test for hazards and contaminants in the environment, and to protect workers and emergency responders

- Source: National Health Security Preparedness Index

Social & Physical Environment Rank: 30% total weight

Population Density/Social Distancing: 10% weight

- Measures: Total population per square mile

- Source: United States Census Bureau

Hospital Beds Available: 4% weight

- Measures: The number of hospital beds per 1,000 people (includes government-owned, non-profit, and for-profit beds)

- Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Health Care Unaffordability: 4% weight

- Measures: The percentage of adults who responded positively to the question, “Was there a time in the past 12 months when you needed to see a doctor but could not because of cost?”

- Source: American Community Survey

Uninsured Rate: 4% weight

- Measures: The percentage of adults age 18 to 64 without health insurance

- Source: American Community Survey

Adult Wellness Visits: 4% weight

- Measures: The percentage of adults who reported that they went without a routine checkup in the past year

- Source: American Community Survey

Child Wellness Visits: 4% weight

- Measures: Compliance with preventative care under the child health component of Medicaid (the number of individuals who received at least one initial or periodic screen as a share of total individuals under 20 years old who are eligible for EPSDT)

- Source: American Community Survey

Sources

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- National Health Security Preparedness Index

- United States Census Bureau

- United States Interagency Council on Homelessness

- American Community Survey

- American Hospital Association

- Innerbody Research

Fair use statement

Innerbody Research is committed to providing accurate and useful health information in order to improve public health and wellbeing. The reason why we invest the time and effort into creating this study and other health-related research and guides is to raise awareness by making information widely available. We hope to reach as many people as possible. As such, please feel free to share our content for educational, editorial, or discussion purposes. We only ask that you link back to this page and credit the author as Innerbody Research, www.innerbody.com.

About Innerbody Research

Innerbody Research is the largest at-home health and wellness guide online, helping over one million visitors each month. Our mission is to provide objective, science-based advice to help you make more informed choices about home health products and services.

Over the past 20 years that we have been online, we have helped tens of millions of readers make more informed decisions involving staying healthy and living healthier lifestyles.

All of our expert writers have advanced degrees in relevant scientific fields. In the cases where our guides and reviews contain medical-related information, all such material is thoroughly reviewed by one or more members of Innerbody Research’s Medical Review Board, which consists of board-certified physicians and medical experts from across the country.

If you have any questions or feedback regarding this research or any other material on our website, you can email us at questions@innerbody.com.

![These States Have the Highest and Lowest STD Rates [2024]](https://innerbody.imgix.net/std-state-map-2022.png?auto=format&ixlib=react-9.4.0&h=174&w=262)